A matter of time

Best-selling author and science writer Dava Sobel spoke on campus on January 23 as part of the University's 2019 Winter Enrichment Program. Photo by Khulud Muath.

-By David Murphy, KAUST News

The best-selling American author Dava Sobel describes herself as a "storyteller who enjoys science." Sobel was born in 1947 in The Bronx, New York City, and grew up in a household full of science inquiry—her mother trained as a chemist and her father was a doctor. From an early age, Sobel was encouraged to pursue science, especially through her burgeoning talent for the written word.

As part of the University's 2019 Winter Enrichment Program, Sobel visited KAUST on January 23 to deliver a keynote lecture outlining the importance of the geographic coordinate of longitude. More specifically, she described how longitude, as a matter of time, has acted as a problem solver for navigational difficulties wholly reliant on precision timekeeping.

The imperative need to 'carry the time'

The former New York Times science reporter and writer of popular expositions on scientific topics began her science writing career in the 1970s, and from 1995 onward she became a full-time author. Her books, which are aimed at unraveling the great mysteries of time and space, include "Longitude" (the story of John Harrison, the self-educated English clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer); "Galileo's Daughter" (about Sister Maria Celeste, the daughter of the famed Italian scientist Galileo Galilei); and "The Glass Universe" (focusing on a group on influential female scientists working at the Harvard College Observatory).

In her 2019 Winter Enrichment Program keynote lecture, famous author Dava Sobel noted how sailors, explorers and navigators throughout history have been able to easily work out latitude, but figuring out longitude has always been more difficult. Image courtesy of Shutterstock.

"Because the Earth is always spinning, there is nothing that stays still in the heavens as a pointer for longitude," she noted. "The whole trick to being able to determine your longitude is to know what time it is in two places at once—where you are and also at a place of known longitude. That was very hard to do for most of human history. In fact, it was impossible, and it's alarming to think that the entire age of exploration was carried out without anyone ever knowing where they were."

John Harrison: the longitude problem solver

The remainder of her keynote covered a broad span of history from the "Age of Sail" in 1571 A.D. up through modern time and our reliance on navigational tools like the Global Positioning System (GPS) and smartphones. Sobel spoke about various historical figures, including John Harrison, the subject of her first book "Longitude."

Following the Scilly naval disaster of 1707— regarded as one of the worst disasters in British naval history that resulted in the loss of four warships and 1,300 sailors—the British government created the Longitude Act of 1714, offering £20,000 (roughly $12 million in today's money) of prize money to anyone who could solve the longitude problem. Harrison eventually won the money after many sea clock prototypes and a long battle with the Board of Longitude and the scientific elite of the day.

'The whole trick to being able to determine your longitude is to know what time it is in two places at once—where you are and also at a place of known longitude. That was very hard to do for most of human history,' noted best-selling author and 2019 Winter Enrichment Program (WEP) speaker Dava Sobel during her WEP keynote lecture. Photo by Khulud Muath.

"Harrison had to prove that his clock could be replicated before he could claim the prize money...Several new additions to the Longitude Act were passed, and one of them stipulated that Harrison would have to build two more timepieces exactly like this to prove that the design could be copied by others," Sobel explained. "The Board of Longitude was actually the world's first research and development agency, and they were empowered to make grants to people who had promising ideas."

"Harrison got so wound up in his fight with the Board of Longitude that he was never able to carry out a final design. He had a plan for a regulator clock that he said would be accurate and would not lose more than one second in 100 days and it would run for a 100 years without maintenance—a claim which seemed laughable, completely ridiculous at the time—and he never had time to build it," she told the audience.

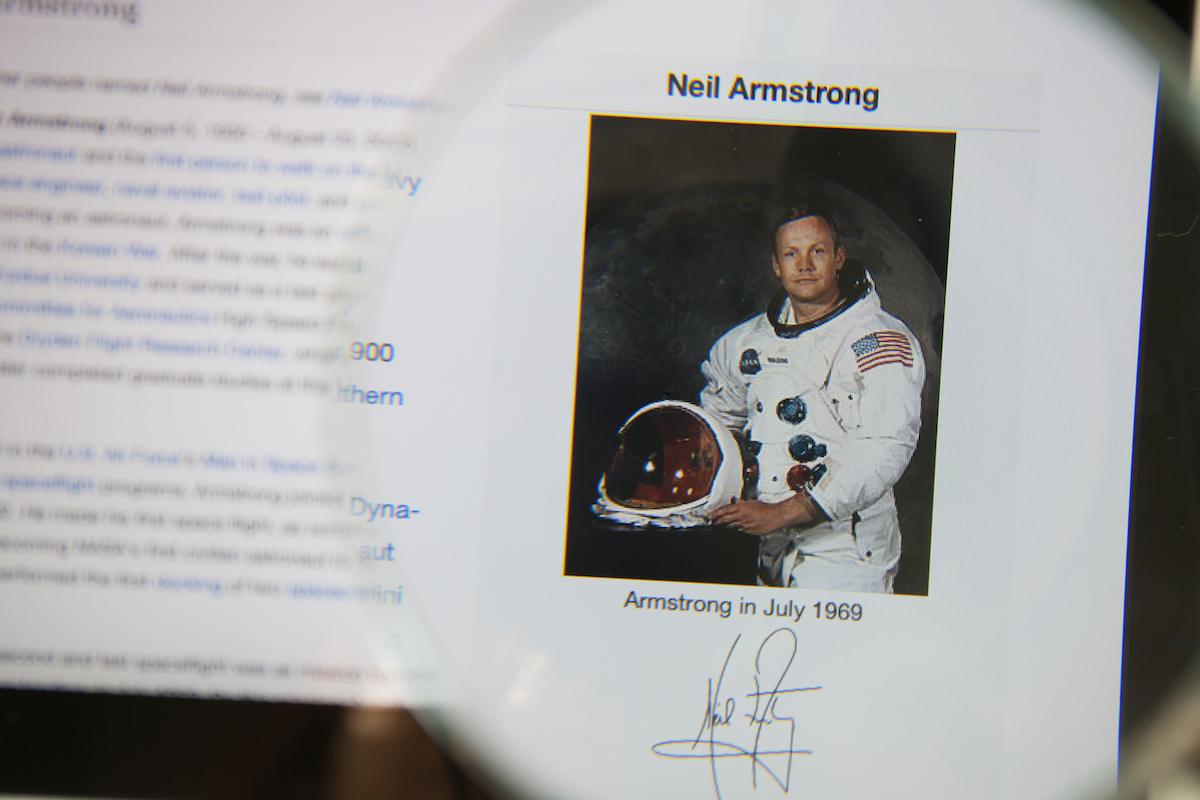

Neil Armstrong, the famous astronaut and the first man to walk on the moon, was an admirer of John Harrison, the self-educated English clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer and figured out how to determine a ship's longitude at sea. Image courtesy of Shutterstock.

"This year we will be observing the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing...and Armstrong appreciated John Harrison long before I came along to write my book," Sobel said. "In fact, when he came back from the moon, and he and his fellow astronauts made their world tour. When they visited the British Prime Minister's residence in London, Armstrong offered a toast to John Harrison as being the person who started them on their journey."

'The future is in our hands'

Sobel maintains that the fate of humanity lies squarely in our hands and the sustainable use of our technologies.

'The future is in our hands,' best-selling author Dava Sobel told the KAUST audience during her 2019 Winter Enrichment Program keynote lecture on campus. 'The planet will get along very well without us if we make it an unlivable place, but for the sake of our own prosperity, that is where we have to put our attention now.' Photo by Khulud Muath.

"The future is in our hands. The planet will get along very well without us if we make it an unlivable place, but for the sake of our own prosperity, that is where we have to put our attention now."

"Nowadays of course nobody needs a clock because we all have GPS on our phones. We know exactly where we are at every moment. We know where we're going. A voice will tell us, 'Turn left, turn right,'" Sobel continued. "But if you think about it, the GPS works on a system of orbiting satellites—so you could think of those as man-made stars. And then satellites are broadcasting time signals from atomic clocks, so the GPS really is the perfect marriage of the two rival systems from the 18th century. It's delightful to think to think what the Board of Longitude would have made of that suggestion."

Related stories:

- Muslim civilization enriches the world

- A race against time

- How does the universe work?

-

Our biological clocks