Doing what was once impossible

Pioneering plastic surgeon Dr. Laurent A. Lantieri delivers a keynote address Monday, April 17, 2017 in the University Auditorium. Photo by Lilit Hovhannisyan.

Reconstructive microsurgery is the transplant of body parts with arteries and veins to damaged areas of the body. Examples include transplanting sections of skin from the tummy to the neck and face or replacing a damaged thumb with a toe. Early practitioners of the medical sciences attempted many of these procedures and documented their work well before 1900. Due to the widespread need for such procedures after World War I, surgeons rapidly developed the protocols, tools and medications to make microsurgeries more routinely successful.

Dr. Laurent A. Lantieri, a modern physician and pioneer who has helped innovate the field of microsurgery, visited KAUST recently as part of the 2017 Enrichment in the Spring program. Lantieri was interviewed live on the University's Facebook page as part of the KAUST Live series.

Lantieri’s high-profile surgical work is focused on improving the quality of life for patients who have experienced disabling injuries or illness in vital areas such as the face and hands. His high-profile surgical cases include a double hand transplant as well as the world’s first full-face transplant.

Lantieri delivered a keynote address as part of his time at KAUST, outlining a brief history of reconstructive microsurgical procedures. He highlighted a historic article about one such procedure known as flap surgery, which detailed the use of a flap from the forehead to replace a damaged nose.

According to Lantieri, World War I and II were times of rapid innovation in the field of reconstructive surgery given the massive numbers of injuries sustained in the conflicts. World War I, for example, was a time when surgeons experimented with the growth of tubes of skin to reconstruct features of the face.

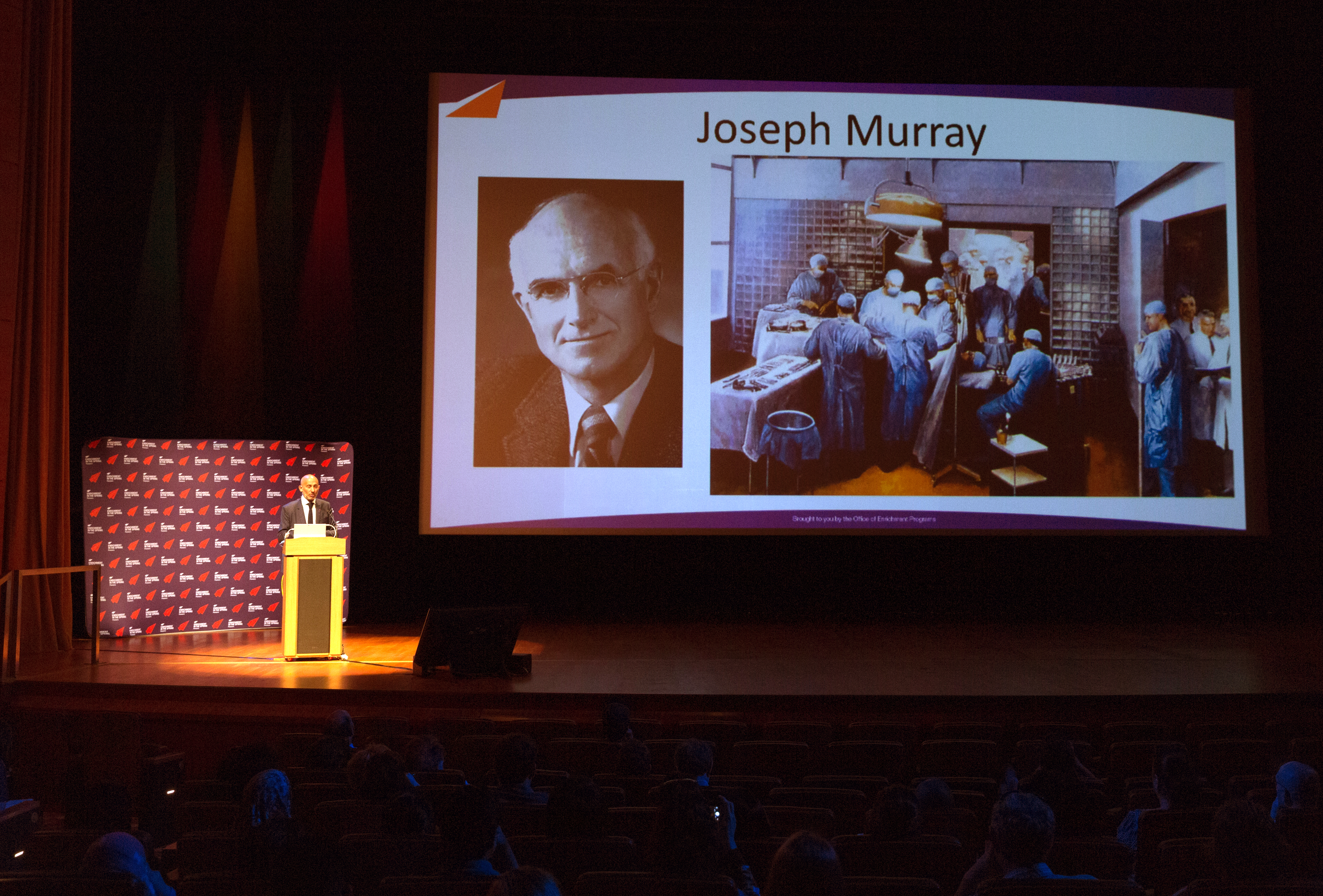

World War II saw the development of skin grafting. In particular, Lantieri cited Nobel Prize winner Peter Medawar for his work on the immune response to skin grafts, as well as the work of pioneering surgeons such as Joseph Murray, who performed the first successful kidney transplant. According to Lantieri, Murray's critical insights about immunology paved the way for many of the transplant procedures we view as routine today.

Vascular surgery is also a key component of successful transplant surgery, according to Lantieri. Though controversial, Nobel Prize winner Alexis Carrel's work led to the success of surgeons like Harry Buncke, who pioneered the suturing of small vessels and ultimately the repair of major injuries.

"For centuries, pioneers were attempting transplants and failing because they lacked the proper techniques and medications," Lantieri said. "For example, the first hand transplant happened in 1963, but it was largely unsuccessful due to the lack of drugs needed to properly blunt the immune system's natural response to non-native tissue. It was only after the development of the right cocktail of drugs that wide-scale allotransplant surgeries became possible."

Apart from the historical and technical aspects of transplant surgery, Lantieri also spoke at length about the professional ethics of transplant surgery in both his KAUST Live interview and during his keynote address.

“We cannot harvest a face or arms without consideration for the deceased and that person's family," Lantieri said. "When we take these items from a donor, we replace them with prosthetic items and a mask to make sure that the body of the deceased is intact. Ethically, we have to treat all patients—donors and recipients—with the same level of respect.”

“Maybe the future is with tissue engineering, in which we will grow animal and human tissues in plant cell scaffolds,” Lantieri opined. "Pioneers such as Harald C. Ott have removed small cells from a donor and have grown new organs, but creating new full-size organs is still not possible. Ultimately I think the future is bioengineering, and I think we will see this come to fruition within the next 10 years or so."

Reconstructive microsurgery is the transplant of body parts with arteries and veins to damaged areas of the body. Examples include transplanting sections of skin from the tummy to the neck and face or replacing a damaged thumb with a toe. Early practitioners of the medical sciences attempted many of these procedures and documented their work well before 1900. Due to the widespread need for such procedures after World War I, surgeons rapidly developed the protocols, tools and medications to make microsurgeries more routinely successful.

Dr. Laurent A. Lantieri, a modern physician and pioneer who has helped innovate the field of microsurgery, visited KAUST recently as part of the 2017 Enrichment in the Spring program. Lantieri was interviewed live on the University's Facebook page as part of the KAUST Live series.

Lantieri’s high-profile surgical work is focused on improving the quality of life for patients who have experienced disabling injuries or illness in vital areas such as the face and hands. His high-profile surgical cases include a double hand transplant as well as the world’s first full-face transplant.

A brief history of transplant surgeries

Lantieri delivered a keynote address as part of his time at KAUST, outlining a brief history of reconstructive microsurgical procedures. He highlighted a historic article about one such procedure known as flap surgery, which detailed the use of a flap from the forehead to replace a damaged nose.According to Lantieri, World War I and II were times of rapid innovation in the field of reconstructive surgery given the massive numbers of injuries sustained in the conflicts. World War I, for example, was a time when surgeons experimented with the growth of tubes of skin to reconstruct features of the face.

World War II saw the development of skin grafting. In particular, Lantieri cited Nobel Prize winner Peter Medawar for his work on the immune response to skin grafts, as well as the work of pioneering surgeons such as Joseph Murray, who performed the first successful kidney transplant. According to Lantieri, Murray's critical insights about immunology paved the way for many of the transplant procedures we view as routine today.

Vascular surgery is also a key component of successful transplant surgery, according to Lantieri. Though controversial, Nobel Prize winner Alexis Carrel's work led to the success of surgeons like Harry Buncke, who pioneered the suturing of small vessels and ultimately the repair of major injuries.

The hands and face

Lantieri talked through not only the transplantation of soft tissue but also of bone. He performs allotransplantation, which is the movement of tissue and bone from donors to recipients. This has been made possible by the many historic advances in vascular surgery and immunology he spoke about earlier in his talk."For centuries, pioneers were attempting transplants and failing because they lacked the proper techniques and medications," Lantieri said. "For example, the first hand transplant happened in 1963, but it was largely unsuccessful due to the lack of drugs needed to properly blunt the immune system's natural response to non-native tissue. It was only after the development of the right cocktail of drugs that wide-scale allotransplant surgeries became possible."

Apart from the historical and technical aspects of transplant surgery, Lantieri also spoke at length about the professional ethics of transplant surgery in both his KAUST Live interview and during his keynote address.

“We cannot harvest a face or arms without consideration for the deceased and that person's family," Lantieri said. "When we take these items from a donor, we replace them with prosthetic items and a mask to make sure that the body of the deceased is intact. Ethically, we have to treat all patients—donors and recipients—with the same level of respect.”

Dr. Laurent Lantieri walks attendees through a brief history of microsurgical procedures during his keynote address Monday, April 17, 2017 in the University Auditorium. Photo by Lilit Hovhannisyan.

The future of surgery might not be 'surgery'

Lantieri dedicated part of his talk to the growth of new tissues as an alternative to transplant and allotransplant (transplant from a donor) procedures.“Maybe the future is with tissue engineering, in which we will grow animal and human tissues in plant cell scaffolds,” Lantieri opined. "Pioneers such as Harald C. Ott have removed small cells from a donor and have grown new organs, but creating new full-size organs is still not possible. Ultimately I think the future is bioengineering, and I think we will see this come to fruition within the next 10 years or so."