3D printing frames a restoration for coral

KAUST scientists are 3D printing bespoke calcium carbonate surfaces that corals can grow on, which may speed up coral restoration.

Coral restoration could become easier and quicker with the use of 3D printing. As the technology matures, it could be used to rapidly and reliably create support structures for corals to grow on.

Coral reefs around the world are suffering from warming oceans and increasing pollution. Reef restoration efforts employ concrete blocks or metal frames as substrates for coral growth. The resulting restoration is slow because corals deposit their carbonate skeleton at a rate of just millimeters per year.

Dr. Charlotte Hauser, KAUST professor of bioengineering, and her team are exploring the use of 3D printing to speed up the process.

“Coral microfragments grow more quickly on our printed or molded calcium carbonate surfaces that we create for them to grow on because they don’t need to build a limestone structure underneath,” said Hamed Albalawi, one of the lead authors of the study. In essence, the idea is to provide the corals with a head start so the reef can recover faster.

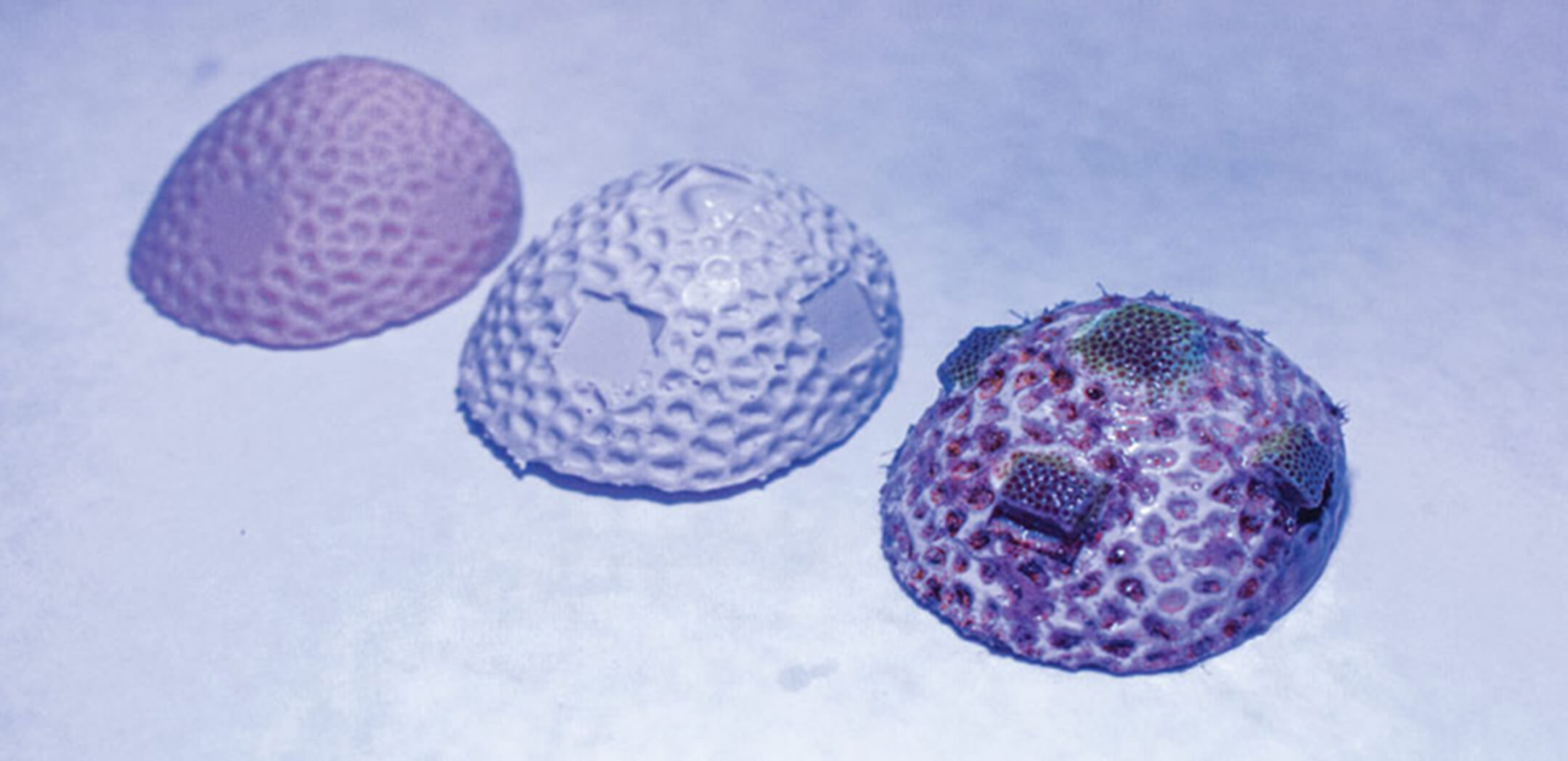

The team developed and tested a new approach called 3D CoraPrint, which uses an eco-friendly and sustainable calcium carbonate photo-initiated ink. Photo: 2021 KAUST / Anastasia Serin

The idea itself is not new. Researchers have tested several approaches to print coral support structures. However, most efforts have used synthetic materials, though work is being done to use hybrid materials. The team developed and tested a new approach called 3D CoraPrint, which uses an eco-friendly and sustainable calcium carbonate photo-initiated (CCP) ink that they also developed. Tests in aquariums have shown that CCP is nontoxic, though the researchers are planning longer-term tests.

Unlike existing approaches, which rely on passive colonization of the printed support structure, 3D CoraPrint involves attaching coral microfragments to the printed skeleton to start the colonization process. It also incorporates two different printing methods, both of which start with a scanned model of a coral skeleton. In the first method, the model is printed, and the print is then used to cast a silicon mold. The final structure is produced by filling the mold with CCP ink. In the second method, the support structure is printed directly using the CCP ink.

The two approaches offer complementary advantages. Creating a mold means the structure can be easily and quickly reproduced, but the curing process limits the size of the mold. Direct printing is slower and lower resolution, but it allows for individual customization and the creation of larger structures.

“With 3D printing and molds, we can get both flexibility and mimicry of what’s already going on in nature,” said Zainab Khan, the study’s other lead author. “The structure and process can be as close as possible to nature. Our goal is to facilitate that.”