Rethinking plastics

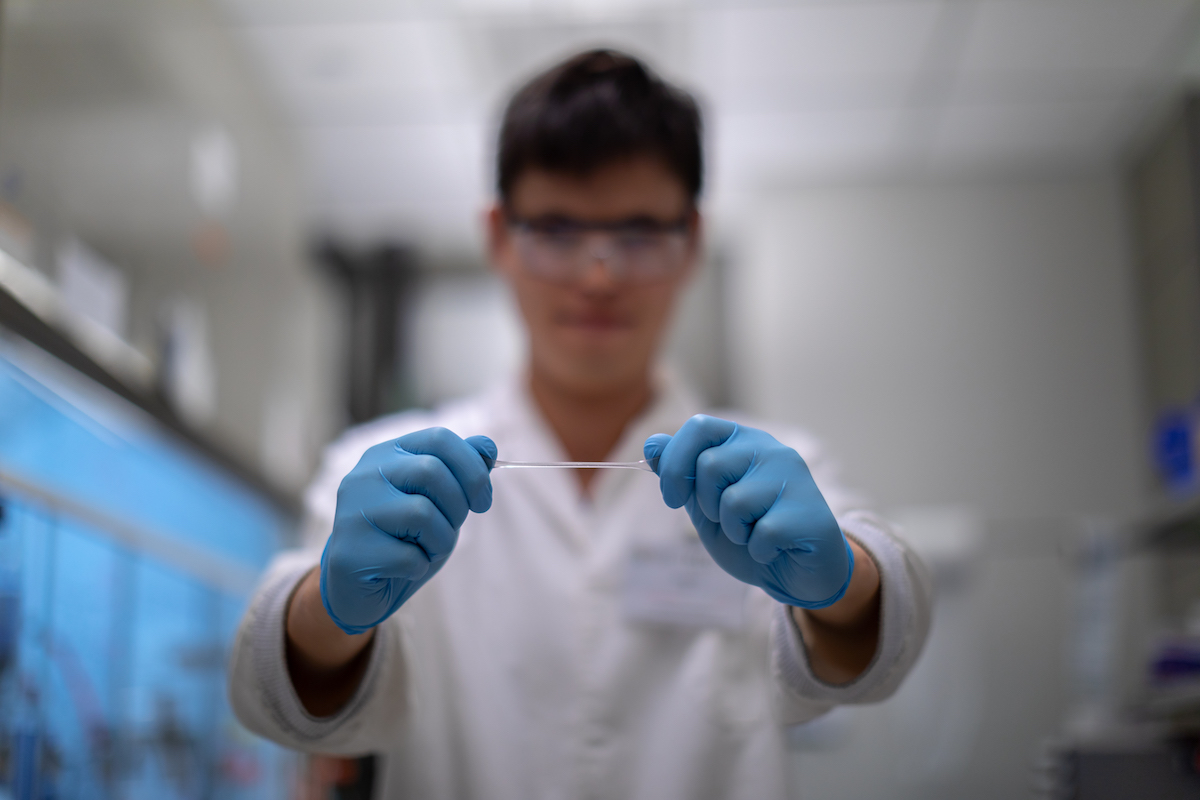

KAUST Distinguished Professors Yves Gnanou and Nikolaos Hadjichristidis and their fellow researchers developed the first metal-free process for making aliphatic degradable polycarbonates using CO₂. The metal-free aliphatic polycarbonate is transparent and highly flexible. Photo by Asharaf AdulRahman.

-By Sonia Turosienski, KAUST News

From plastic wrap to car tires, we demand a lot from our plastics—elasticity, strength, flexibility and recyclability. The ability to manipulate these qualities has made plastics into a diverse and almost ubiquitous material. The omnipresence of plastics, however, has grave implications for the environment and especially for the world's oceans. The United Nations Environment Programme predicts that by 2050, there will be as much plastic in the ocean as there are fish.

'White pollution' worldwide

Recently, there has been a change in the public's awareness of and concern for plastic pollution, also called "white pollution." In addition, many countries are releasing copious amounts of CO₂ into the atmosphere, contributing to global warming. While reducing plastic consumption and encouraging reuse is crucial, Yves Gnanou, KAUST distinguished professor of chemical science and acting vice president for Academic Affairs, working with Nikolaos Hadjichristidis, KAUST distinguished professor of chemical science, developed the first metal-free process for making aliphatic degradable polycarbonates using CO₂.

KAUST Distinguished Professors Yves Gnanou and Nikolaos Hadjichristidis' research groups are working to develop polymeric materials that are more sustainable at the point of production. Photo by Asharaf AdulRahman.

The KAUST researchers work in the lab on their green chemistry process that does away with the use of toxic metals to produce aliphatic degradable polycarbonates using CO₂. Photo by Asharaf AdulRahman.

Doing away with metal

Gnanou and his team developed an alternative green chemistry process that does away with toxic metals in favor of two non-metallic reactants—an ammonium compound that helps the coupling reaction between CO₂ and epoxides and a boron-based compound that activates the latter monomer.

The polycarbonate developed by KAUST researchers (pictured above) was made using CO₂ in a metal-free process. Photo courtesy of Prof. Yves Gnanou; taken at the University of Maastricht.

Recently, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report outlining that global warming must be kept to 1.5 degrees Celsius to avoid drastic changes to our ecosystem. The report added that "[g]lobal net human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide would need to fall by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching 'net zero' around 2050."

KAUST Distinguished Professors Yves Gnanou (right) is shown here in the lab on campus working with a researcher. Photo by Asharaf AdulRahman.